When it’s time to change: managers, drivers of flexibility.

10 December 2018

Managers help make any organizational change or evolution successful while also bringing about systemic changes for the people involved.

Article written by Rémy Texier

10 December 2018

Managers help make any organizational change or evolution successful while also bringing about systemic changes for the people involved.

Article written by Rémy Texier

In a state of constant flux, organizations cannot but note how their capacity to support their employees and help them evolve is becoming a key factor to success, if not to survival. Although most recent organizational models (shared leadership, freedom-form company) are prompting us to rethink the missions and even the very raison d’être of middle-management, the (proximity) manager is ideally placed to support his team members in the most efficient way. PROSCI’s research shows that for 67% of all collaborators, the voice of the direct manager has the most impact with respect to everything that concerns their everyday life and working environment. In a sense, managers help make any organizational change or evolution successful while also bringing about systemic changes for the people involved. This role, often undermined by organizational optimizations, is therefore somehow restored. Simply put, it implies supporting the continued development of the team(s).

It is thus clear that the manager’s mission is to help the organization, i.e. all of its members (including himself/herself), overcome any obstacle or resistance factors as quickly as possible in order to turn what was envisioned for the future into tangible reality (the kind of evolution that has been proposed and desired).

To this end, the manager will have to:

- Communicate, i.e. be capable of translating the reasons underpinning the change into a practical program of priorities and activities for each collaborator.

- Be a liaison officer connecting each and every one involved in a given change initiative (“greasing the wheels” of change circuits)

- Walk the talk, leading the change by example

- Identify resistance factors and properly deal with them

- Support the development of his/her collaborators throughout the transition

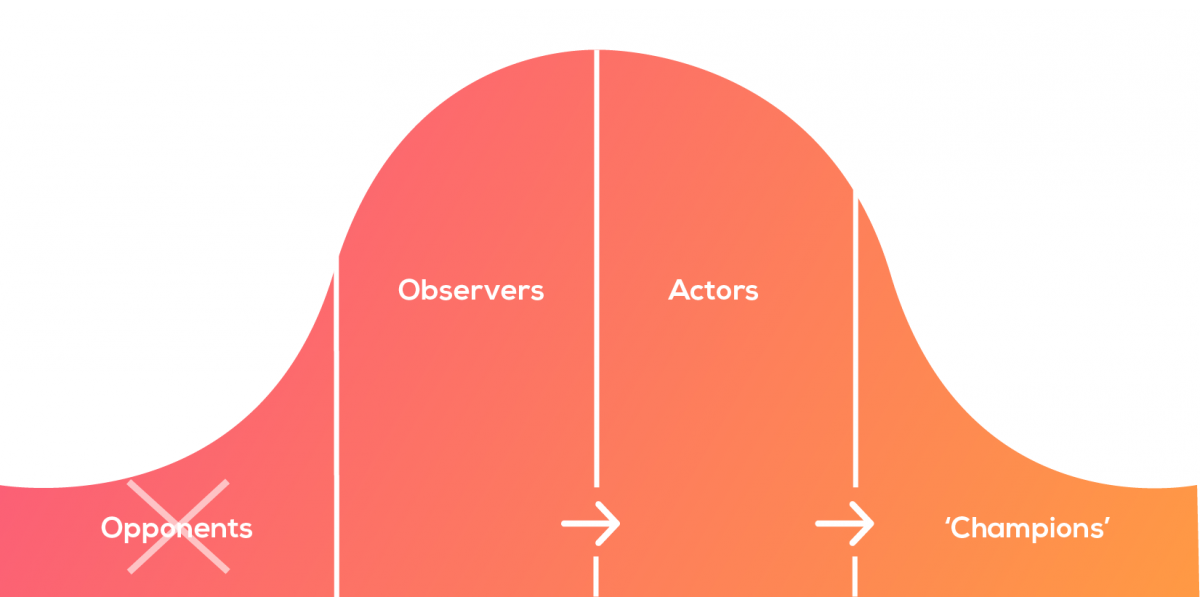

Each individual copes with change in his/her very own way, which depends, inter alia, on her/his personal profile and current circumstances. The following graph illustrates how this will lead him/her to either become a “champion” (convinced driver), an “actor” (fully agreeing on the envisioned change), an observer (not fully convinced, taking a wait-and-see approach) or an opponent (clearly against the change). Managers will tailor their actions to meet individual needs - bearing in mind that the ultimate goal is to help them become “actors” or “champions”.

Priority should in this sense be given to the group of so-called “observers” with the aim of making them “actors”. The reasons why it is so important to prioritize this group are manifold: way too much energy is required to try to convince opponents at all costs, resistance factors are expected to be less difficult to deal with, it can be an advantage to use the “group effect” after growing the number of “actors”. The question now is: in practice, how should a manager go about this task?

The systems field suggests we take a combined look at the group/team level and the relationships between each individual and the group. The rest of this article will focus on the latter. To better understand why it is so important to research the relationships between the group and its individual members (and not the relationships between individuals), consider the following real-life opposite situations. The first one refers to a setting where the group “cheers on” the individual, who can then leverage his new-found emotional energy to expand resources, just like a champion in a sports stadium. At the other end of the spectrum is a situation in which the individual himself hinders the group performance.

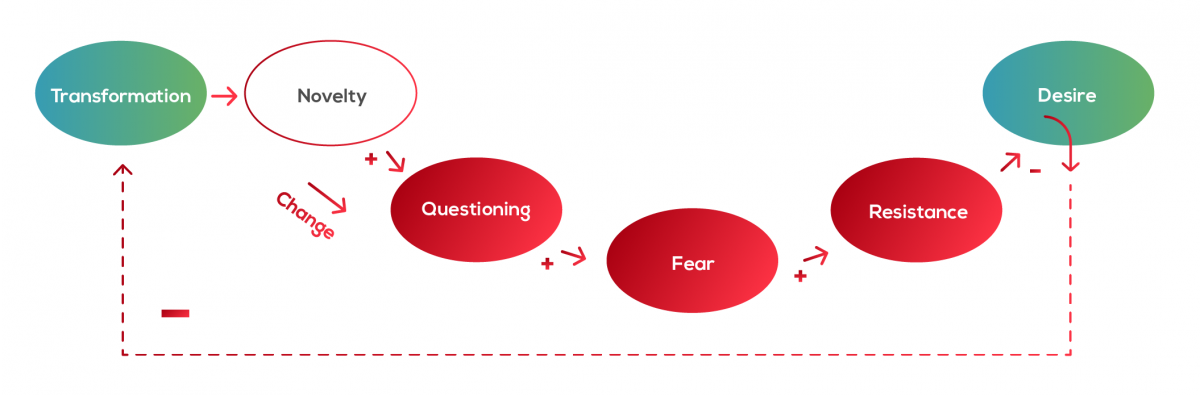

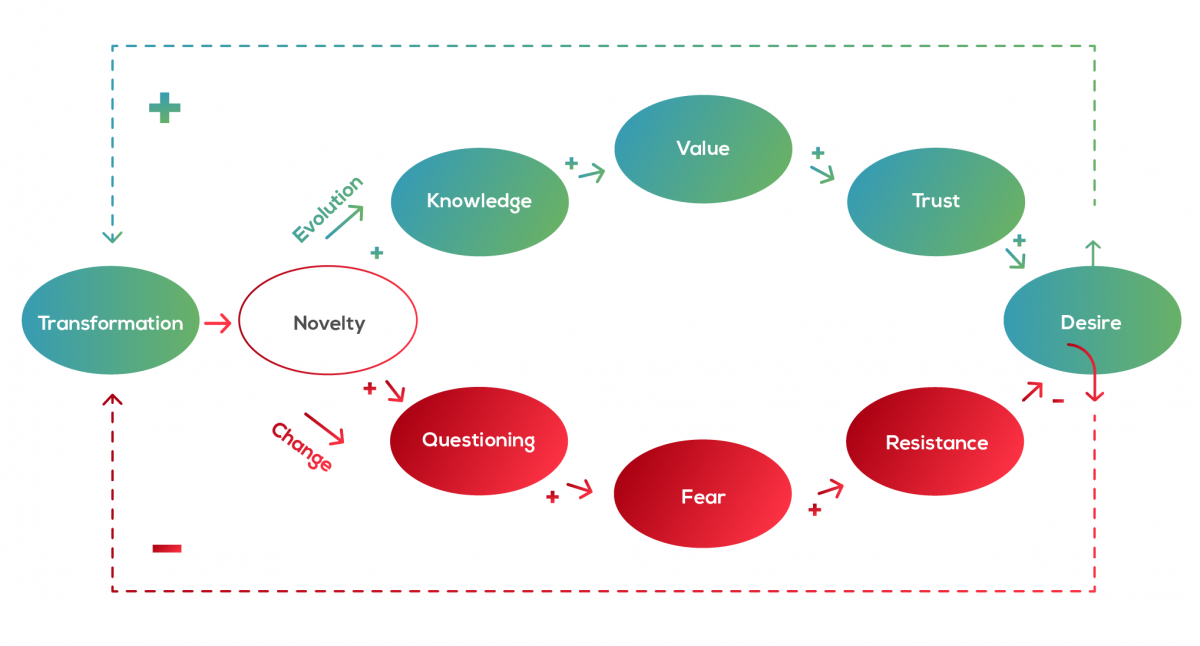

The following diagrams illustrate how the group influences the individual throughout the whole process of internalizing the change.

At stage one, an “observer” of the change can perceive the transformation as something likely to question his habits, taking him out of his comfort zone and making the future much harder to predict. This in turn fuels a feeling of fear that feeds resistance, thereby contributing to the willingness to change.

In the next stage, the transformation follows an alternative path and what was once new and threatening is now perceived as an opportunity to gain valuable and fresh experience, hence knowledge. This increases the individual’s value while boosting his/her confidence, thus encouraging him/her to pay greater attention and be more receptive.

Everything hinges on the person’s state of mind at the time they discover the novelty (change). The group (team) they belong to is also their conditioning system. The kind of energy they feel from the team may or may not facilitate their accepting the change as a favorable evolution for themselves.

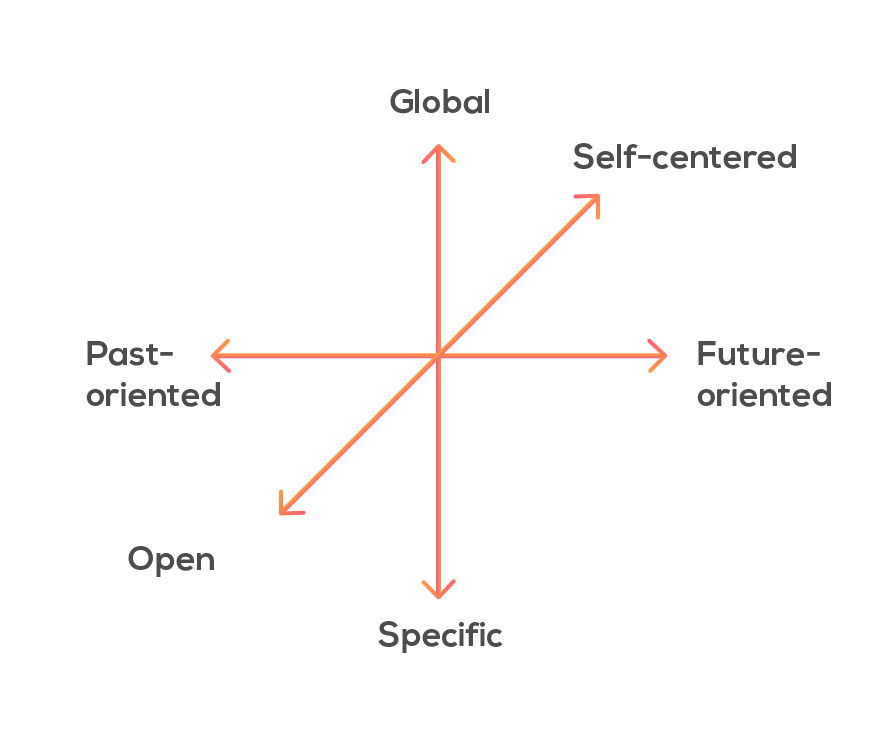

The whole art is to leverage the group energy to create the best conditions for everyone to evolve and by recurrence, contribute to amplifying that collective energy. For this to occur, the manager will have to examine his/her collaborators’ behavioral patterns. The two aspects underlined here below must be systematically taken into account given that they are central to the support process.

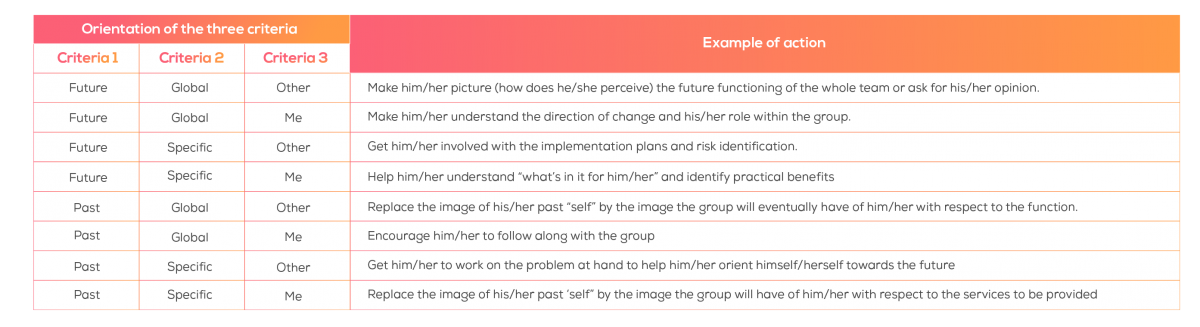

1- Is the person past or future-oriented? (the objective is to better understand their perception)

2- Is the person more global or specific in their way of going about things? (the objective is to determine which information is important for them)

Other behavioral qualities can be combined to these in order to “embed” the group effect into the collaborator’s perception:

3- Is the person self-centered or open-minded and approachable (the objective is to understand to what extent external judgments can affect the collaborator)

4- Is their point of contact internal or external? (to discern the future)

5- What ways of relating to others are predominant? (independent, proximity work, collaborative)

6- How or on what basis do they sort information? (people, activities, places, or others)

7- Etc…

The complexity inherent to the human condition makes it impossible to map out all possible scenarios. Based on the three first criteria, the following example (graph and box) illustrates how such an analysis can help managers identify the actions best suited for driving things (and above all, people) forward.

It all comes down to determining which actions can prompt the collaborator to see novelty as a promise of enrichment instead of a painful episode of self-examination, and therefore help him/her usher in the next step of his/her evolution. These actions complement the support plan for the manager, true agent of “flexibility” within the given organization.